Oh No! Not another greek alphabet. Do I have an obsession with them? Maybe.

Just like Pi, Phi is a symbolic representation of Golden Ratio. Golden Ratio, what? I have never heard of it.

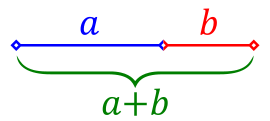

We find the Golden Ratio when we divide the a line into two parts such that the ratio of the longer part to the shorter part is equal to the whole length divided by the shorter part.

\[\varphi = \frac{a}{b} = \frac{a+b}{a}\]

And the magic begins,

\[\varphi = \frac{a}{b} = 1 + \frac{a}{b}\] \[\varphi = 1 + \frac{1}{\varphi}\]

Did I mention anything about recursion?

\[\varphi = 1 + \frac{1}{1 + \frac{1}{1 + \frac{1}{1 + \frac{1}{\ddots}}}}\]

Nevermind, let’s calculate its value.

\(\varphi \) is a solution of quadratic equation \(\varphi^2 - \varphi - 1 = 0\)

\[\varphi = \frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2} = 1.6180339887…\]

Another irrational number.

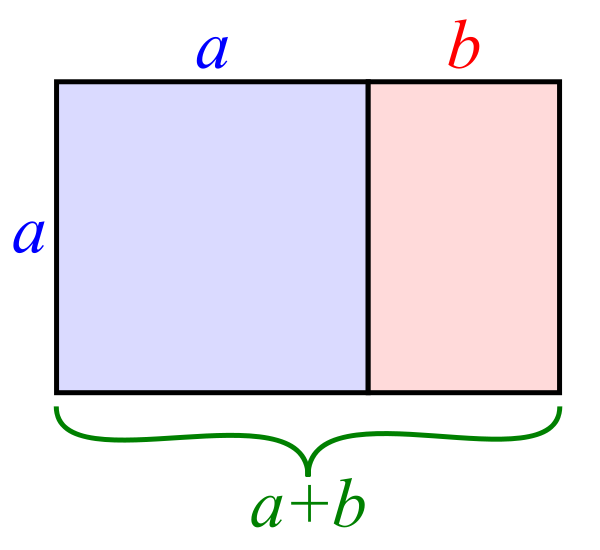

Inspired by the 1D line we can extend this in 2D. A 2D rectangle with side length \(a + b\) and \(a\). Following the properties of Golden Ratio, this rectangle is known as Golden Rectangle.

But there is more to it. What if we subdivide the rectangle into a square and another rectangle and do it until we get two squares? Adding to it if we construct a spiral by pivoting at the corner of the square and turning it quarter in a continuous fashion, we will get Golden Spiral. It is an ever-expanding spiral.

Now let’s look from a different direction — bottom up. Consider two unit squares, combine them along the side. Attach a square of side length equal to the length of the larger side of the previously formed rectangle. We will get a similar pattern again. But if we look at the side length of squares we will find an engaging pattern.

1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, …

Length of the side of the next square is equal to the sum of the previous two. Remember Fibonacci Series. When we take the ratio of two successive numbers from the Fibonacci Sequence then their value is very close to Golden Ratio.

| A | B | B/A |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 1.5 |

| 3 | 5 | 1.6667 |

| 5 | 8 | 1.6 |

| 8 | 13 | 1.625 |

| 13 | 21 | 1.615 |

As we approach towards infinity this ratio converges to the Golden Ratio.

Enough of mathematics Square. We understand, Golden Ratio has myriads of secrets. Why should we care?

This divine proportion is all around us but its knowledge is confined to some mainstream recognition. Just like air — it’s there but we can’t see it. Similarly, Golden Ratio is omnipresent — from nature to music to architectural design. This tool is used by sculptors and artists to achieve remarkably accurate proportion and aesthetic compositions.

Throughout history, we can find many instances of phi. The first guy was Luca Pacioli, a Franciscan friar who wrote a book called De Divina Proportione back in 1509, which was named after the golden ratio. He did not tell about the aesthetics of Phi, instead the book focused on the Vitruvian System and its allegiance with golden ratio. Leonardo da Vinci was close friends with Pacioli. Da Vinci used this secret math in many of his famous paintings including Monalisa. Ancient Greek architecture used the Golden Ratio to determine pleasing dimensional relationships between the width of a building and its height, the size of the portico and even the position of the columns supporting the structure.

Phi is also said to be common in nature. Flower petals often come in Fibonacci numbers, such as five or eight, and pine cones grow their seeds outward in spirals of Fibonacci numbers. The ubiquitous nature of the Golden Ratio with its diverse and engaging application have made Phi another mathematical marvel.